Rear Admiral Grace M. Hopper, USN, Ph.D., born December 9 1906, is a really interesting person.

I ran into information about her a while back while researching the origin of the expression “debugging”. Turns out that she denied coining the term, but it got me reading and I have to say… why don’t we know more about her? She did so much for computer science! Also, I’m pretty sure no coder besides her have a guided missile destroyer named after them.

I know there was a Google doodle made in her honor but, at the end of the day, a lot of developers don’t even know her name… or they think that she “only” created COBOL, which is not entirely true.

I wanted to write something about her back then, but that’s also the point in my life where I realized that I would make a terrible biographer. However, I finally decided to give a shot at summarizing a few of her accomplishments related to computer science. So here I won’t be spending any time on other subjects. I’ll let you keep on reading elsewhere if you want more information regarding her early life, military feats, awards or education.

Interesting fact, while I was finishing my article, a documentary called “Queen of Code”, directed by Gillian Jacobs, was released. You should give it a watch!

The Havard Mark Computers

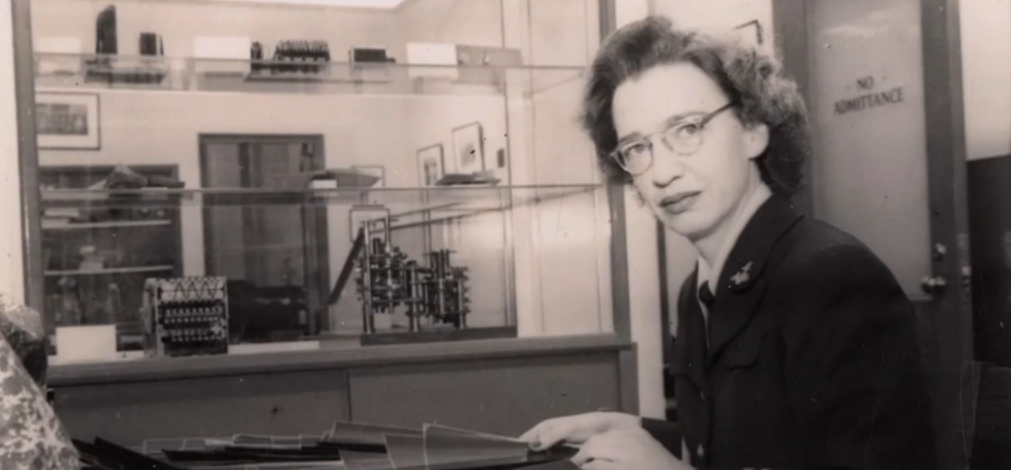

In 1943 Hopper was teaching mathematics at Vassar, but she decided to take a leave of absence and volonteered to serve in the WAVES - the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service. She did well during training and was sent to Harvard University where she was assigned to work as part of the Mark I Computer programming staff.

“We did coding, we ran the computer, we did everything. We were coders.”

Grace Murray Hopper in a 1980 interview

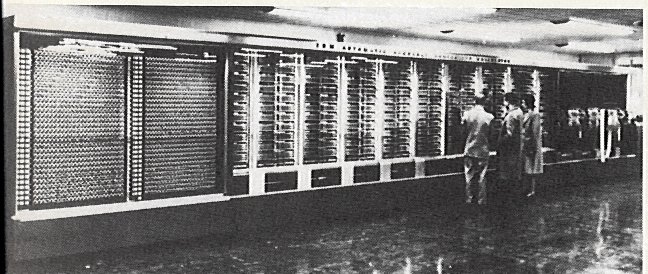

It was a time of punch cards and switches, but this computer was trully helping the military by running large amount of mathematical operations. It was notably used to figure out the viability of implosions for the Manhattan Project.

After the war, she remained in the Navy and worked as a research fellow at Harvard for a few years on the Mark II (a paper-tape sequenced calculator) and Mark III (an electronic computer with magnetic drum storage).

UNIVAC & The First Compiler

In 1949 she joined the team working on the UNIVAC I, the second commercial computer produced in the US. This is where she started working on her compiler, the A-0 System. At a time where every programmer would produce assembly code, it was revolutionnary. In 1952 she had an operational version of her single-pass compiler, but she ran into scepticism from the industry.

“Nobody believed that, I had a running compiler and nobody would touch it. They told me computers could only do arithmetic; they could not do programs. It was a selling job to get people to try it. I think with any new idea, because people are allergic to change, you have to get out and sell the idea.”

Grace Murray Hopper

It took a while, but this idea was finally accepted. Grace Hopper and her team iterated and released new versions of the compiler. In the end, it was the A-2 compiler that would be the first to be used extensively, leading the way for even more improvements and the creation of new programming languages.

MATH-MATIC & FLOW-MATIC

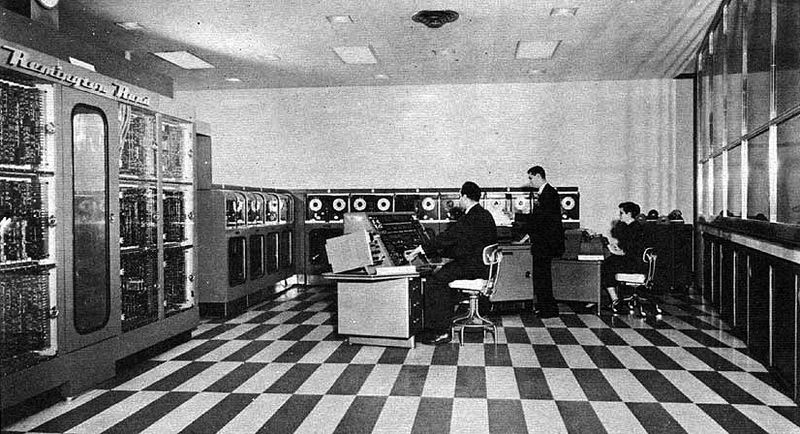

In 1954 Hopper was named the first director of automatic programming at Remington Rand. She and her team worked on a new compiler, the AT-3 that was commercially called “MATH-MATIC”.

They also created FLOW-MATIC, also known as B-0 (Business Language version 0). It was realized based on the observation that customers processing business data were not comfortable with mathematical notation.

“I kept calling for more user friendly languages. I’ve always tried to do that, that’s why I want these other languages that are aimed at people. Most of the stuff we get from academicians, computer science people, is in no way adapted to people.”

Grace Murray Hopper in a 1980 interview

In 1953, Hoper proposed that problems could be expressed with English keywords. Her company’s management at the time decided that the idea would be unfeasible and discarded it. Despite this, in early 1955, Hopper and her team wrote a specification for such a programming language and implemented a prototype.

“It’s always easier to apologize than to ask permission.”

Grace Murray Hopper

This language was FLOW-MATIC, the first language to use English keywords that facilitated its use in business settings. This was proved useful and IBM even released COMTRAN (Commercial Translator) in 1957 following the same principle. It’s also worth mentioning that FLOW-MATIC was also the first language to separate the description of data from the operations made on it.

If you are curious, here is the brochure and how the syntax looked:

That’s right, I have a FLOW-MATIC Gist now.

Influence On COBOL

In 1959, Grace Hopper and a group of colleagues started to push for a common language for business applications. This was aimed to reach a greater compatibility among vendor systems. With this goal, they organized the Conference on Data Systems Languages or CODASYL.

Following its objective, the organisation designed COBOL (COmmon Business-Oriented Language) to be a compiled English-like computer programming language aimed to be used by businesses. It reached a great level of adoption and is still in use today, mostly in banking.

All the current programming languages at the time , such as AIMACO or COMTRAN, had some kind of influence on COBOL . However it is notorious that COBOL was mostly based on the previous programming language design work made by Grace Hopper. Several elements of FLOW-MATIC were even incorporated into COBOL, including the separation of input and ouput or the idea of dividing a given program into sections.

This is why she is refered to as “the (grand)mother of COBOL”.

“If you take the FLOW-MATIC manual and compare it with COBOL 60 you’ll find COBOL 60 is 95% FLOW-MATIC. So the influence of Commercial Translator in fact was extremely small.”

Grace Murray Hopper in a 1980 interview

Standards & Portability

In the 1970s, Hopper was part of an effort to implement standards for testing computer systems and components. The point was to be able to use a same program on various computers, which was often impossible at this time, and conversion from a vendor to another would cost a fortune.

Her main focus was on COBOL, both on the language and the validation of compilers. The result was an increased portability and better documentation.

Influence On Best Practices

During her career, Grace Hopper pushed for reusability and collaboration between developers. She was said to encourage programmers to collect and share common portions of programs to reduce errors and duplication of effort. This seems even more visible with the idea within FLOW-MATIC of dividing a program into sections and her work on standards as mentioned above.

She was also very visionnary in seeing the great potential in making computers more accessible to businesses and management groups by making programming languages more expressive.

An interesting point is that she was very active in trying to get corporations to prefer distributed systems over large mainframes. This implied a large shift in mentality as giant general purpose systems were the norm.

I could see people were going to need these things and the amount of information would increase. And I still think it’s going to increase even more. I don’t think we’ve even begun to recognize how much we are going to have to do with these computers.

Grace Murray Hopper in a 1980 interview

To Conclude

Rear Admiral Grace M. Hopper, USN, Ph.D. passed away in 1992 at age 85.

The most important thing I’ve accomplished, other than building the compiler, is training young people. They come to me, you know, and say, ‘Do you think we can do this?’ I say, “Try it.” And I back ‘em up. They need that. I keep track of them as they get older and I stir ‘em up at intervals so they don’t forget to take chances

Grace Murray Hopper

Quick References

Here is a list of what I read through to write this post. I’m not mentioning the countless wikipedia pages and random websites.

- http://www.cbi.umn.edu/hostedpublications/pdf/McGee_Book-4.2.2.pdf

- http://www-gap.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/Biographies/Hopper.html

- http://www.cs.yale.edu/homes/tap/Files/hopper-wit.html

- http://books.google.ca/books?id=QmfyK0QtsRAC&q=hopper#v=snippet&q=hopper&f=false

- http://www.cs.yale.edu/homes/tap/Files/hopper-story.html

- http://archive.computerhistory.org/resources/text/Remington_Rand/Univac.Flowmatic.1957.102646140.pdf

- http://archive.computerhistory.org/resources/text/Oral_History/Hopper_Grace/102702026.05.01.pdf

- http://archive.wired.com/science/discoveries/news/2008/08/dayintech_0807

- http://archive.computerhistory.org/resources/text/Knuth_Don_X4100/PDF_index/k-8-pdf/k-8-u2776-Honeywell-mag-History-Cobol.pdf

- http://www.dvq.com/oldcomp/oldads.htm

- http://discover.lib.umn.edu/cgi/f/findaid/findaid-idx?c=umfa;cc=umfa;rgn=main;view=text;didno=cbi00011

- http://fivethirtyeight.com/features/the-queen-of-code/

If you found that I made a mistake or that something is not clear, please let me know in the comments with a reference to a correction and I’ll fix the article as soon as possible.

Since you scrolled this far, you might be interested in some other things I wrote: