There are many ways to set up a startup software engineering team, and many teams follow the same progression and encounter the same issues. In this article I’ll do my best to showcase the different options and their limitations.

Note that there is no perfect organisation that will work for all situations… only tradeoffs and choices you’ll have to make depending on your circumstances. I’m not showcasing the logical progression. Instead I want to highlight how a team organisation can progress over time when facing limitations of each step.

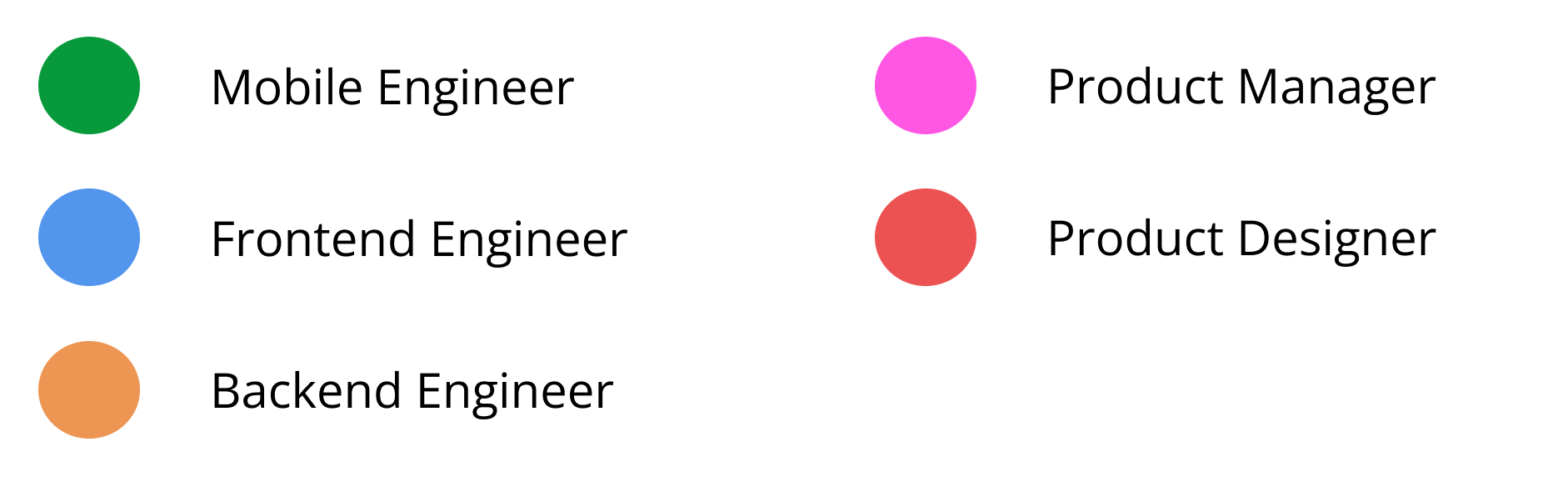

For our example, let’s assume we have a post series A startup building a B2B SaaS with 18 engineers, 3 PMs and 2 product designers. To ship the product, they need backend, frontend as well as native mobile apps. They have some infrastructure work, but as they are mostly on the cloud they don’t have anyone fully dedicated to this just yet. Apps are standard native apps (Swift, Kotlin), frontend is one SPA with React and the backend is a NodeJS monolith.

Scenarios

I’ll represent people by circles, with the color representing their main technical skills. This is a significant approximation, but I hope you’ll still get the main ideas!

Technical Teams

Initially everyone was in the same team, but as they grew, the company needed some structure. They decided to split the team by technical stack. Frontend engineers with frontend engineers and so on. The product team being smaller, they decided to stay together as well.

This setup works well for the engineers at first. Being surrounded by your peers working on the exact same stack feels great and helps improving one’s craft. Each person gets to work on the entire project, so they get to see a lot of different parts of the product which is nice.

However, after a while, some problems start to appear. It turns out that most projects involve all 3 skills (front, back & mobile), so every project end up being a cross team endeavour. Frontend engineers start to complain that APIs are not ready on time, mobile engineers are not pleased that said APIs are optimised for the web platform and not for apps. Finally, backend engineers feel disconnected from the product and pressured by other team members to deliver faster.

On the product side, it’s the same thing. Having to communicate with 3 full teams for all projects makes it hard to build anything and get clear feedback on what is possible or not. Engineers are shifting domain often and don’t really build deep knowledge of any particular part of the product, so it feels like starting all over with every project. It is frustrating to not have a clear engineering counterpart to challenge ideas and discuss roadmaps.

Squads

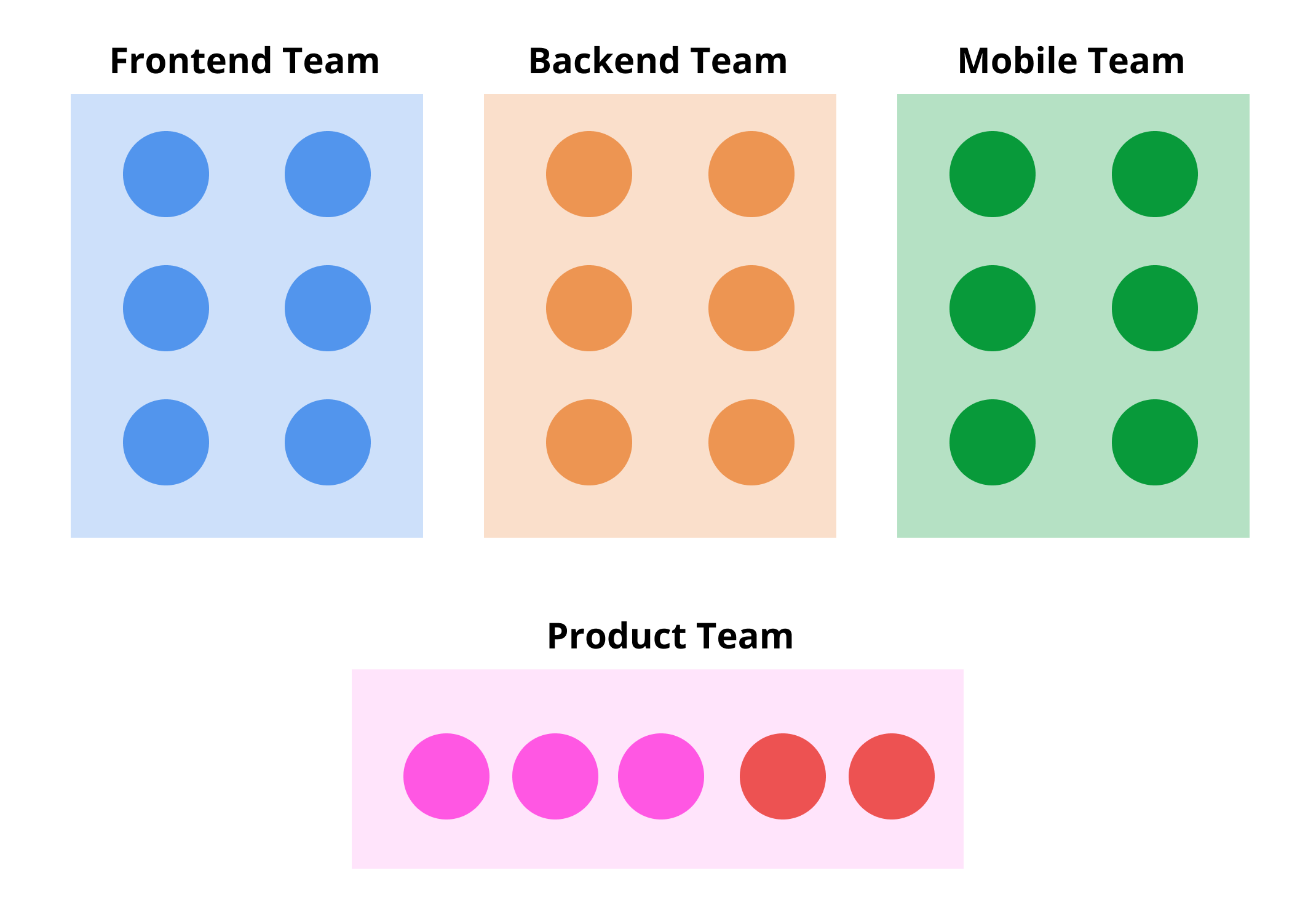

The company decides to reorganise in order to address those issues and they group people around a business domain. Inspired by what was shared by Spotify a while back, they call them “squads”.

There are now 3 squads, A, B and C, each of them with enough people to tackle projects in their scope. Squad B is missing a product designer though, but it’s fine as the one from squad C is going to help 30% of their time.

Again, this works well for a while. Having a real team dynamic around solving business problems feels more directly impactful. Squads have their own KPIs, so seeing lines go up after a release is rewarding. Having colleagues with different skills helps broadening all team members’ own skillset.

After a year like this, teams start to slow down and problems start to appear. The fact is that many technicals projects didn’t get done and technical debt started to pile up. Since engineers were in their squads focused on features, the more “core” technical work was left to the side. It is indeed quite hard to figure out who should work on large-scale engineering project, so the complex framework update didn’t get done, the flaky end-to-end tests are not getting addressed and the test suite is now taking 55 minutes to run when it was 3 minutes just a couple of months ago.

Engineers feel more isolated in their stack and the pressure to ship more features is always present. They don’t even have the time to create some kind of plan to address it, because their entire day to day is focused on the squad - meaning solving direct business problems.

Product managers love the new dynamic and the fact that their team can accomplish anything. However they understand that it can’t continue forever and that the more technical debt is added, the harder it’ll be to get anything done. Plus, thanks to the new team dynamic, they are more empathetic of the engineers’ situation.

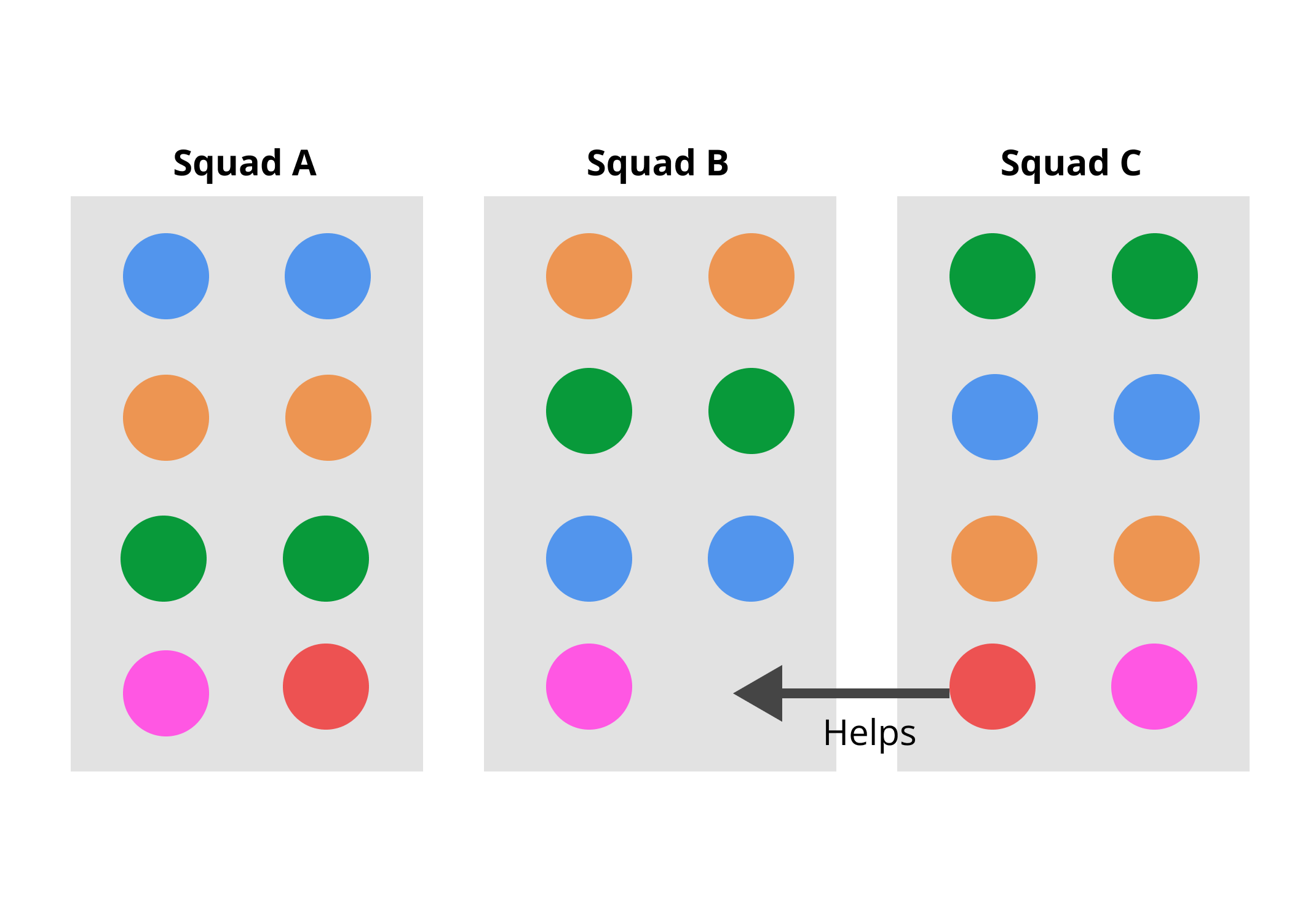

Chapters

Luckily, they already knew about the concept of chapters. In other organisations they can also be called “community of practice” (CoPs), and the idea is to have a transversal grouping of people based on their shared technical knowledge. In this situation it means that all frontend engineers are grouped in the “Frontend Chapter” and so on.

The 3 chapters are then created, alongside the appointment of 3 “chapter leads”, highlighted with a darker border in the diagram. They are the main point of contact of the chapter and are responsible for making things happen.

The effects are quickly visible: the chapter leads advocate for more “core” time allocated by every squad. The novelty helping, many project are getting done and the technical debt is slowly getting back under control. The chapter organises technical talks, helping to level up all members on very specific part of the stack and the team gains in seniority faster. All good technical ideas are shared faster across teams and consensus on topics like linting or what lib to pick are reached faster and without conflict.

On the product side however it’s a different story. After a couple of months, the product manager realise that they can’t really count on their team’s engineer time as they are often working on some other project for the chapter. Planning anything is getting impossible, and prioritising projects is a struggle: should we focus on updating the framework or on a new feature asked by a big client? While all projects eventually are business projects, measuring the impact of each takes forever as we are comparing quite different topics.

This kickstarts the beginning of a constant fight for engineering time between the squads and the chapter. This is pleasant for no one, and some teams end up with documents stating things like “Alice will spend 23% of her time on the chapter tasks this quarter, and Bob only 11%”. There is more and more tracking to make sure those commitments are respected, slowing everyone down.

Dedicated Core Team

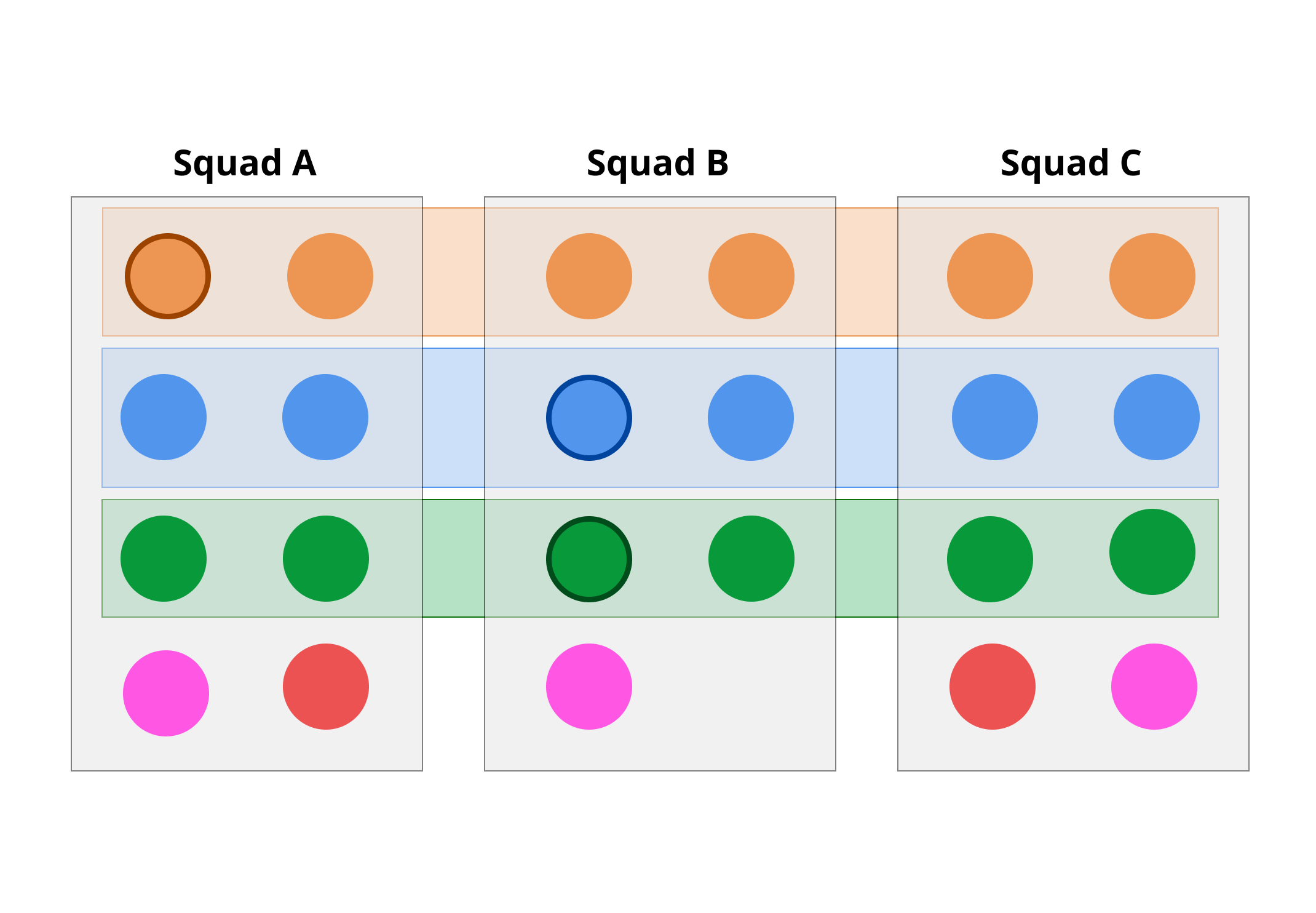

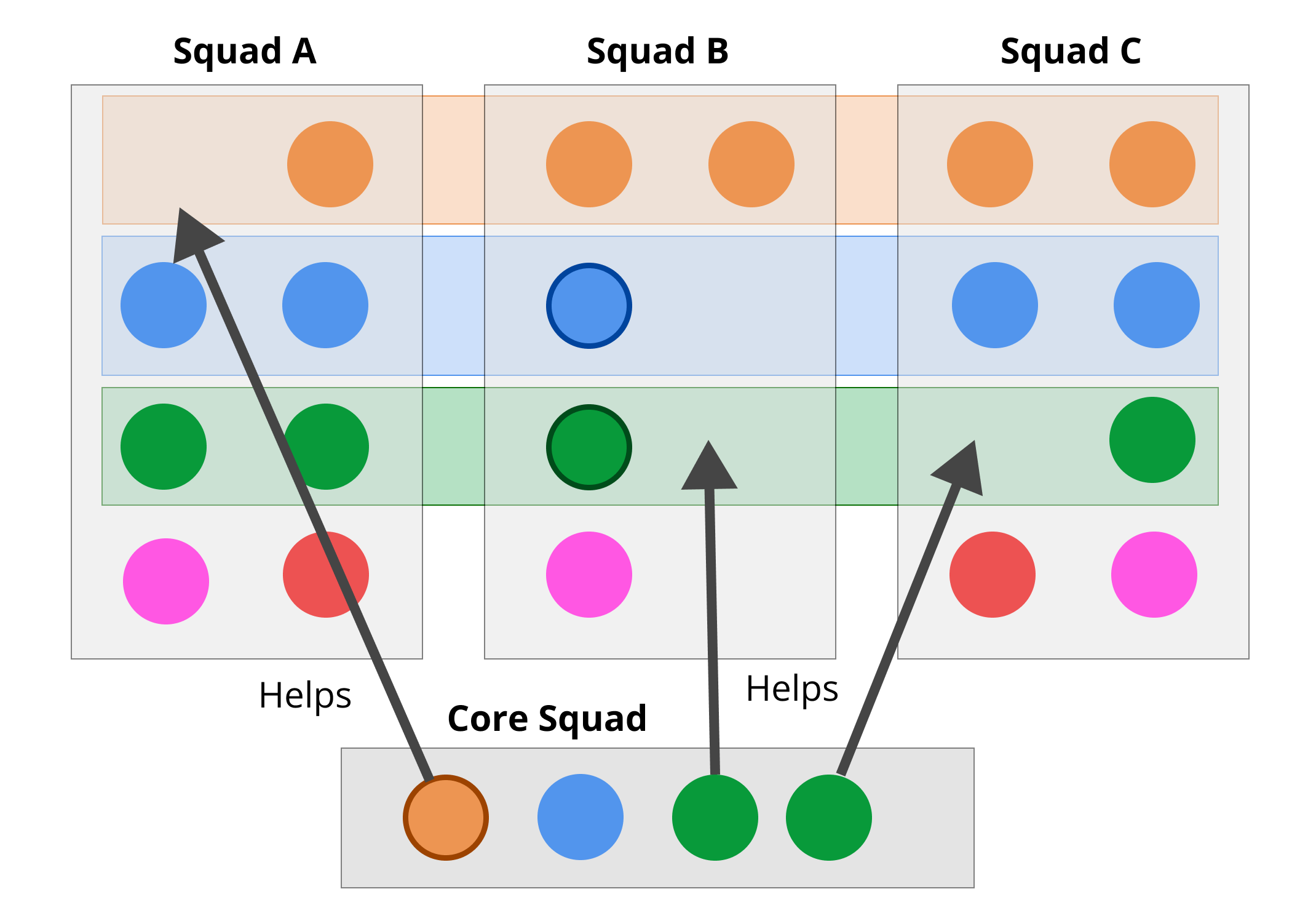

After a few months of conflict and arguing about 5% of an engineer, everyone agrees on switching things up again. The company then creates a “Core Squad”, meaning a brand new squad dedicated to working on those transversal technical projects. Squads A, B and C are now referred to as “Product Squads” and the new Core Squad is called a “Platform Squad”.

Defining who should be in there is hard. Should it be the most senior people? Moving them away from product squads would be detrimental to the business… but the challenges of the core team will be very complex! After many debates, they end up with this organisation:

The backend lead is going to move to the core squad and will act as the global lead, as backend is the most complex and critical part of the company’s stack. 2 mobile engineers moved to the core team as both iOS and Android needed to be represented. However they will be helping their old squads that will now have to deliver slower on one platform. One frontend engineer is moved away from squad B, but this should mostly be fine since the chapter lead is there. However squad A is in trouble by design as there is only 1 backend engineer and they lost their most senior engineer. To adjust for it, the backend chapter lead agrees to help.

There are still some people shared across teams, but people are happy that the constant arguing over time is over, and everyone can get back to either building features or working on transversal tech projects. Engineers in product squads are happy to not really bother thinking about solving technical debt as the core squad will take care of it.

The chapters remain active with meetings and discussions cross team, but only the engineers within the core squad are actually writing code. This means that for most people this is more a forum to share ideas and discuss technical topics, which is already pretty good.

As you guessed, after a while some new problems start to emerge.

Turns out that the backend lead never really had the time to help their old squad, given the amount of work leading the core squad required. Because of this fact, squad A is now way behind schedule. Both frontend and mobile engineers are completely stuck waiting for new APIs from the now alone backend dev, who is now asking to move to the core squad to be left alone.

Clients were complaining that both mobile platforms are not moving at the same pace, so the mobile engineers ended up spending much more time in their product squad than expected and didn’t get much done on the core side.

Another problem is that the frontend engineer who moved to the core squad is not enjoying the work. It was fun at first, but they wanted to build features, not update libraries, benchmark tools and clean up debt.

Finally, the entire core squad is disgruntled by the attitude of the other engineers. The rest of the team stopped caring about transversal technical work and just assumed it’d get solved by the core team. This makes the core squad create more and more process to get everyone to work as they think they should. The whole thing creates a rift between the technical experts focused on long-term quality on one side, and the product engineers focused on shipping customer value on the other.

One Shot Projects

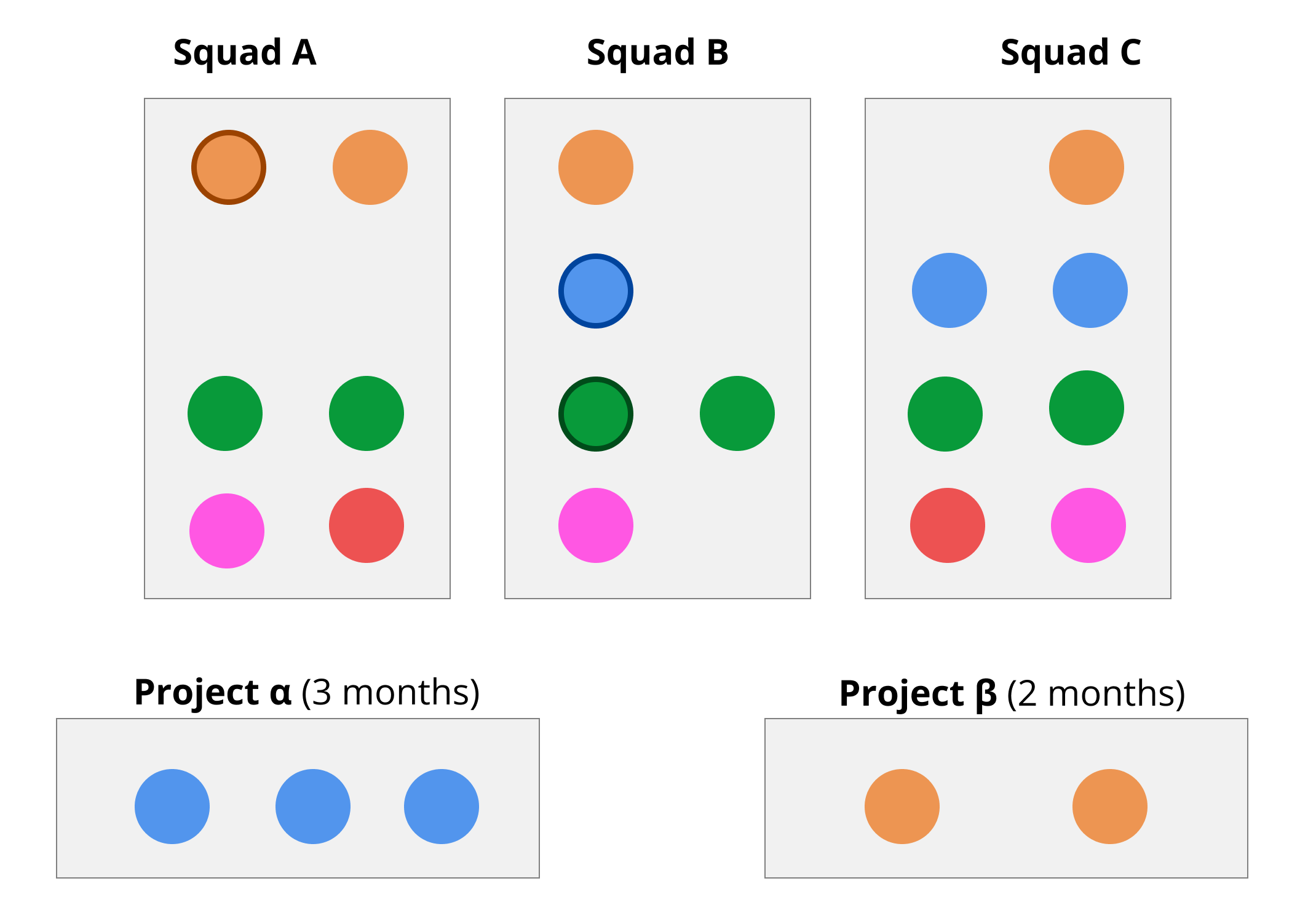

The core squad approach is rolled back and the company tries doing a per-project approach instead. This means that if there is a big technical project, some people will be assigned to it for a couple of months and then go back to their team.

Two large projects, α and β are started, taking some people away for a while.

This makes things immediately clearer: projects are well defined, resources are allocated for a given amount of time and that’s it. This gives everyone confidence and work keeps going.

However after just a month, some limitations start to show.

First of all, project β might take 4 months instead of 2. Is this ok? Should we shut it down or add more time? No one really knows, so no decision is made… meaning the project continues without adjustments.

Then, since project α requires so many frontend engineers, the product squads are struggling to get anything done. Everyone agreed beforehand to focus design work on mobile apps for now, but the reality is that it is not working out. To address this issue, the team decide to move one person from α back into squad A.

Another month passes, and it’s getting worse.

As expected, project β is not done at all… except now there is already 2 months of work done and it feels really bad to cancel. So the company decides to bite the bullet and agree to spend the two extra months.

Project α with their missing engineer is now late as well. Adding 2 months to account for it would address the impact… but some engineers start to share that they don’t want to spend 5 months on a technical project like this. They prefered their product squad work and would prefer getting back to it. To address this, one team member from project α is switched out with someone from squad C. This messes up with squad C’s timeline, as well as slowing down project α because the new engineer needs to be onboarded. Instead of adding 2 months, they decide to add 3.

In the end:

- Project α finishes in 7 months. The engineer who stayed for the entire duration is quite burned out.

- Project β shuts down after 3 months. Turns out that it was more complicated than expected and they should have changed the scope, but since the project was defined very precisely after many internal debates they couldn’t. The time is mostly wasted,

After a while, it appears that project α needs some changes, but since the team disbanded no one is available to do it. This triggers complex governance discussions, and the initial engineer that was burned out by the project has to do the update.

Staff Engineers + Chapter Work

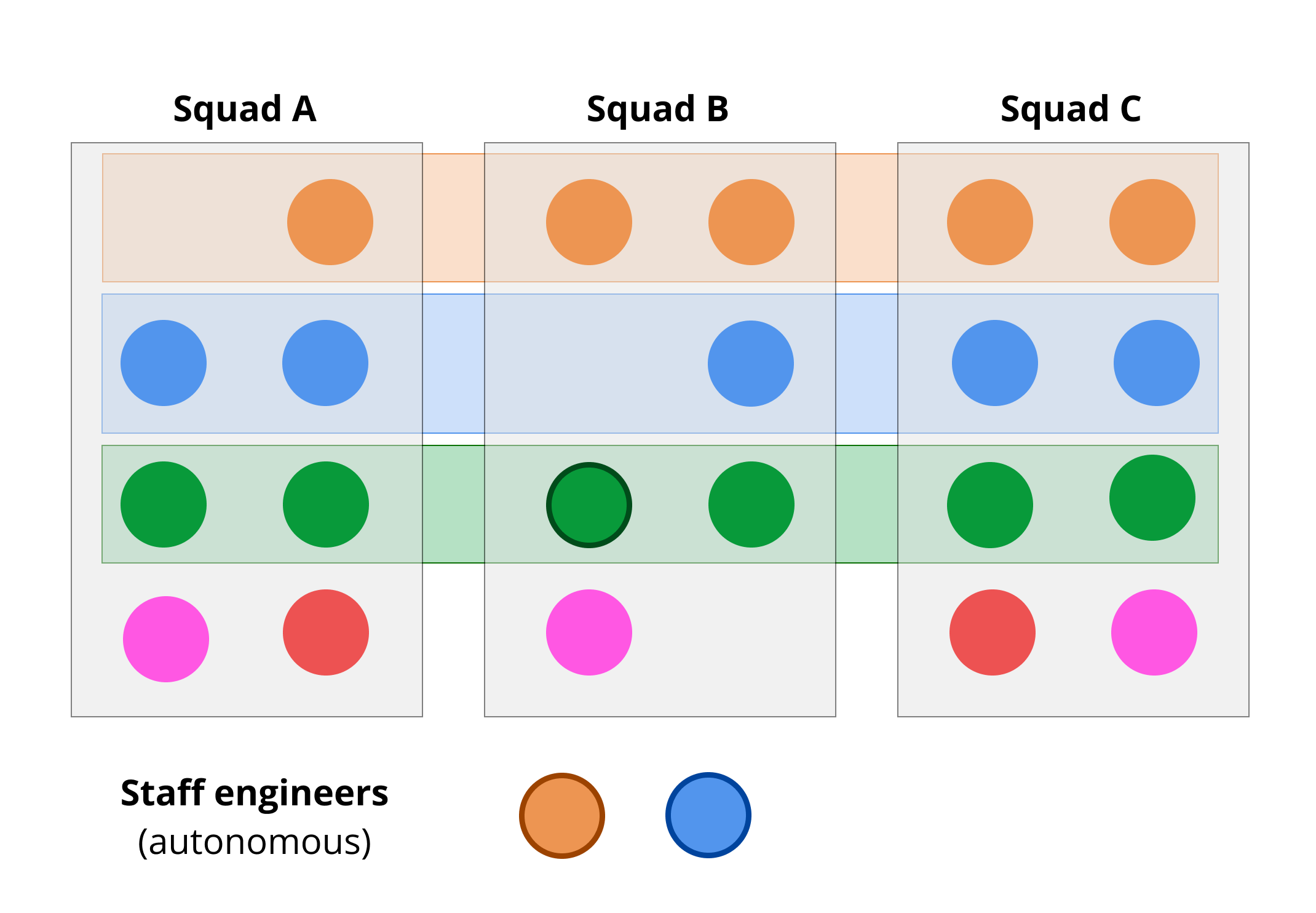

After this project α / β struggle, the company decides to change its approach and introduce the concept of staff engineer.

There are many definitions shared online, and it can vary from company to company, but they decide that they would be their most senior engineers and not bound to a squad. This means that those engineers are very autonomous and can move around the organisation to be the most impactful… sometimes acting as an individual contributor, other times being mostly a force multiplier.

On top of this, the company brings back chapters and chapter work and it is agreed that engineers will spend ~20% of their time on chapter work. Everyone agree to not nickel and dime this percentage, instead focusing on the global velocity. The difference from before is that now the staff engineers can help frame the work and make sure everything goes well.

It was decided that there was no need to extract a mobile staff engineer, because the reality is that the stack is quite manageable already compared to backend and frontend. This is due to the smaller size of people working on each stack (3 on iOS, 3 on Android - vs 6 on web) and how the apps were created later in the lifetime of the company, meaning built with better choices and practices from the start.

This organisation works pretty well. The backend staff helps their old squad until someone from squad B moves to squad A to absorb the very high priority work. The frontend staff can work on a big React update that was making everyone struggle. The staff engineers also organise “update days”, where a few engineers from each squad gather to update dependencies, read changelogs and add tests.

It’s Never Over

I could stop here, since I personally really like the staff+chapter setup… but it also has limitations. For instance it puts a lot of pressure on the staff engineers. It’s also not an easy job and requires a great technical sense, good communication skills as well as a solid business understanding, meaning hiring them is also a big challenge.

Then, what happens if you add or remove a few engineers? And we haven’t even talked about leadership and management in this article!

Hopefully this gave you ideas to experiment in your own team, and maybe you recognised your current organisation!

Since you scrolled this far, you might be interested in some other things I wrote: