Okay. Let’s start by saying that I’m a developer that does mostly web stuff.

This means that a majority of the code I write will end up displaying something in a browser. Of course I do interact with APIs, write background jobs, add some security, optimize databases and so on… the point here is that, professionnally, I do not write entire projects that have nothing to do with a web app.

My friend André on the other hand has a different background as he mainly develops games. One evening we started talking about how complex it would be to create an online multiplayer game from scratch. Being the web guy, I felt that I should know how all this was supposed to work… after all, the multiplayer happens over the internet, right?

I Can Code That With My Eyes Closed…?

On paper it seemed pretty simple.

People connect to a server. This server keeps the game board and broadcasts it to everyone when needed. Each player keeps some kind of state on its side for caching. Everything related to drawing the game board as well as UI should be handled by the client.

Of course I knew it couldn’t be that simple and I was 100% sure I was disregarding most of the problems that can occur when creating an online game.

I already blogged about how side projects are the best response to such situation, therefore at that point I pretty much had to create some kind of game to try it out!

Stack

Time being a factor, I didn’t want to go all out game development with C++, Unity or something like that. Instead I kept it in my “safe” zone by using technologies I had a bit of experience with:

- NodeJS (for the server)

- HTML5 Canvas (to display the game board)

- Websockets with Socket.io (to make it fast)

Building The Game

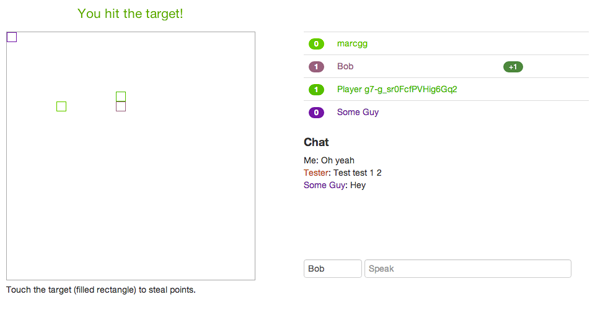

I wanted a simple game so that I could focus on the online aspect of it. The rules I came up with are:

- There are n players represented as squares on a board.

- 1 player is the target and earns 1 point per 30 movements.

- If another player hits the target, she becomes the target and win 1 point.

I also added a simplistic chat system so that players could talk to one another during the game.

The first version of the multiplayer code was pretty simple:

- When the player connects she gets the latest version of the game board.

- Each time the player moves it sends an event to the server that updates the world and broadcasts it to everyone connected.

- Client side javascript renders the board in the canvas at each change.

This is when I started to see why it wouldn’t be as simple.

Oh Wait. Problems.

Speed

My first version was hosted on Heroku and lagged like crazy. This is because right now Heroku doesn’t support Websockets and forces socket.io to fall back to its polling mode. After some research I moved to DotCloud and got an impressive boost in speed.

I also had to rewrite a lot of code using Express because it would make deployment way easier.

Now that hosting and basic interactions were a bit more optimized, I started to see another problem: passing around the whole board was still too costly network-wise.

At that moment of development the board was just a JSON object containing all the players, their names, positions, scores and other meta data regarding the game. It seemed pretty small but it wasn’t, and as the game would grow the problem would only get worse.

The solution here would be to only broadcast what changed instead of redrawing everything. This was annoying because it meant that you need to be able to draw the board from scratch (when you connect) as well as incrementally (while you play). Twice the logic.

I also noticed a lag for the player’s own actions. This was because it would always go via the server before updating the board. As a matter of fact there wasn’t even a board on the client side, just its rendering on the HTML5 Canvas.

Soooo to fix this the client code should also be able to know the state of the world and update it locally.

Fun, Gameplay & Complexity

A game needs to be fun, or else there is no point. And a couple of laggy squares moving around is clearly not fun. This seems trivial, but when you spend your time working on web apps, you don’t spend a lot of time thinking about whether the app is fun or not. Making it efficient, fast and user friendly is complicated enought!

I added some rules and gameplay elements to make it feel more like something one would like to play, including:

- Feedbacks when you get hit

- Scoreboards during game

- Invicibility frames when you get hit

- Board boundaries

- Changing a player’s name

- Tweaks in the player’s speed & size

It’s also good to know that some of the gameplay elements are based on constants. For instance you always move of X, and your player is Y pixel-wide. When you get hit you are invicible for Z frames and so on. To tweak it I had to add a debug mode to change everything while playing to quickly see how it felt.

All these changes made my simple game complex and it became harder to maintain the code, even only after something like 6 hours of work in. I had to throw away a lot of code and start again fresh.

Concurent Access

When you have a lot of players connected and modifying the same board, you’re bound to run into some concurent access issues. For instance let’s say two players touch the target at the same time. Who gets +1 point?

To fix this I hacked together a basic mutex system to handle the simple problems that kept on happening. This did the trick after an hour of code, but it wasn’t something I’d put in production!

Conclusion

Overall I’m pretty happy with the results. Even with my lack of experience in the subject I still got something running and gained a better grasp of why game developers tremble when you mention online multiplayer.

Now I think the next step would be to design a game taking the constraints discovered into account in order to simplify development. You don’t want a game where precision and timing is key. You could instead create a massively online turn-by-turn game and save yourself major headaches while still producing something fun! It all depends if you seek a technical challenge or if you just want to create a cool project.

Also I’ll need to find a graphic designer because my game looked like shit, but that’s another story.

Since you scrolled this far, you might be interested in some other things I wrote: